I apologize for this being a day late, but I am now in my last few weeks of the semester and entering the time when I have more work than time or sanity. So, today, instead of pondering what makes good writing good, I'm going to review a movie I saw over the Thanksgiving holiday: Dreamworks' Rise of the Guardians.

I feel like this isn't as lazy as it could have been, since the movie is based on a book series by William Joyce, who also helped make the movie. The books are good, and you all should read them, but I'm going to talk about the movie.

Short response: I thoroughly enjoyed it.

By now, you should know that I reward "awesomeness" highly, which might not be my best trait. The movie was awesome, kind of an Avengers for children. I also really enjoy mythology of all kinds, so it was interesting to me to see how the mythological figures of Santa, Sandman, Easter Bunny, Tooth Fairy, and Jack Frost would interact, and what they would see as their purpose. Why deliver toys? Why take teeth and leave coins?

I was impressed by the depth they put into the protagonist, Jack Frost. From the trailers, it seems like Jack is not a central part of the story, that he's a wild, rebellious kid with no cares in the world, but that's not true. He has anxieties and fears that make him a fairly interesting character, and also allow for a fascinating (at least to me) parallel between him and the antagonist, Pitch. This film is actually a good example, I think, of the shadow: a character that is similar to the hero in many ways, but has fallen. A perfect example from the world of superheroes is Peter Parker/Spider-Man and Eddie Brock/Venom.

It makes it cooler to my English-major brain that the "shadow" in Rise of the Guardians is literally a shadow, namely, Pitch Black, the Nightmare King.

Other things I liked: the movie has a character who doesn't speak, who is still dynamic and compelling. I love characters who manage to have a strong presence without much dialogue. I also liked the bright colors, very imaginative and dreamlike, that sparked memories of childhood and the wonder, hope, and dreams that came with it. Also, I have never wanted to go ice skating or have a snowball fight so bad in my life.

Do I think it was as good as How to Train Your Dragon? No, I do not. The characters weren't as compelling, and the dialogue didn't sparkle as much. But I also think what we have here is a new story, with its own place in the world. It was a cute movie, and I would definitely see it again while it's still in theaters.

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

Monday, November 19, 2012

Gimmicks: Use and Abuse

Happy Thanksgiving, all! I hope you're spending time with friends and family and a great deal of food. First off, I want to mention my publisher's Kickstarter campaign. It ends November 26, so time's running out. Support us. Tell your friends.

There are a lot of awesome movies coming out this holiday season. Lots of great books, too. Some of them have some excellent ideas behind them, which I would even characterize under "awesome". However, I feel like these interesting ideas can hinder a story instead of help it. They become "gimmicky" and the story never is able to move past them.

What do I mean? Let's look at several children's movies. The first is Hotel Transylvania, a movie about a hotel where monsters can go to feel safe from humans. I thought it was a cute movie, but when I left, I said, "I wish they didn't use so many monster gags." I felt like the whole story was only a frame to hang jokes about ghosts, skeletons, Frankenstein, mummies, etc., on. The movie was a string of jokes and references, leaving plot and characters to be underdeveloped. I'm not saying they weren't there, but they didn't shine. Plot was simple and predictable, and characters felt flat and equally predictable. The idea was clever and the movie, riding on its gimmick, was okay. But it could have been more.

I want to compare this to films like Toy Story, Monsters Inc., and the recent Disney movie Wreck-It Ralph. These three movies (note that 2 of them are Pixar) have unique and clever "gimmicks" as the frame for their stories: toys are alive and move around when you're not looking at them, monsters scare kids because it's their job and they're actually scared of children, and arcade game characters are doing a job and may not like what they've been programmed to do. These movies do make references and jokes about the gimmick, but what sets these movies apart is how compelling the characters are.

What it comes down to, what it always comes down to, is the characters and how they interact. The "gimmick" of the frame is clever and intriguing, but the story digs deeper. The story is no longer about the gimmick, but about the characters. The "gimmick" may be prevalent, but only as a way to display the characters and their motivations. For example, Toy Story is more about jealousy, shown by a favorite toy's (Woody) fall of popularity by a new, fancy toy (Buzz Lightyear), and friendship, as shown when Woody and Buzz get lost and have to find their way home.

The gimmick is not the focus of the story; the interactions are. I guess the rule of thumb here is: can the same story be told in a different setting, with a different frame, and still be interesting? If not, it's relying on a gimmick. Toy Story would still be interesting because the draw is the relationship between Woody and Buzz. The same goes for the other films.

What does this mean for writing? Come up with a fantastic idea, something unique and compelling. Something other people don't think of. We're writers; we're creative. This is our job. But don't stop there. Figure out how the compelling idea would mold compelling characters, and then tell their story. It will be much more interesting.

There are a lot of awesome movies coming out this holiday season. Lots of great books, too. Some of them have some excellent ideas behind them, which I would even characterize under "awesome". However, I feel like these interesting ideas can hinder a story instead of help it. They become "gimmicky" and the story never is able to move past them.

What do I mean? Let's look at several children's movies. The first is Hotel Transylvania, a movie about a hotel where monsters can go to feel safe from humans. I thought it was a cute movie, but when I left, I said, "I wish they didn't use so many monster gags." I felt like the whole story was only a frame to hang jokes about ghosts, skeletons, Frankenstein, mummies, etc., on. The movie was a string of jokes and references, leaving plot and characters to be underdeveloped. I'm not saying they weren't there, but they didn't shine. Plot was simple and predictable, and characters felt flat and equally predictable. The idea was clever and the movie, riding on its gimmick, was okay. But it could have been more.

I want to compare this to films like Toy Story, Monsters Inc., and the recent Disney movie Wreck-It Ralph. These three movies (note that 2 of them are Pixar) have unique and clever "gimmicks" as the frame for their stories: toys are alive and move around when you're not looking at them, monsters scare kids because it's their job and they're actually scared of children, and arcade game characters are doing a job and may not like what they've been programmed to do. These movies do make references and jokes about the gimmick, but what sets these movies apart is how compelling the characters are.

What it comes down to, what it always comes down to, is the characters and how they interact. The "gimmick" of the frame is clever and intriguing, but the story digs deeper. The story is no longer about the gimmick, but about the characters. The "gimmick" may be prevalent, but only as a way to display the characters and their motivations. For example, Toy Story is more about jealousy, shown by a favorite toy's (Woody) fall of popularity by a new, fancy toy (Buzz Lightyear), and friendship, as shown when Woody and Buzz get lost and have to find their way home.

The gimmick is not the focus of the story; the interactions are. I guess the rule of thumb here is: can the same story be told in a different setting, with a different frame, and still be interesting? If not, it's relying on a gimmick. Toy Story would still be interesting because the draw is the relationship between Woody and Buzz. The same goes for the other films.

What does this mean for writing? Come up with a fantastic idea, something unique and compelling. Something other people don't think of. We're writers; we're creative. This is our job. But don't stop there. Figure out how the compelling idea would mold compelling characters, and then tell their story. It will be much more interesting.

Tuesday, November 13, 2012

Awesomeness

First off, there is a week left in my publisher's Kickstarter campaign. Show interest! Tell your friends! We'll all thank you if we can make our goal.

Second, I want to talk about awesomeness in writing. When I say "awesomeness" I mean a very specific trait. I don't mean what you, as the writer, like. I know a lot of people who geek out over Renaissance literature, and while writing that into a novel will be fine and dandy for them, I don't think it would count as awesomeness. So, what is awesomeness, and why should writers care about it?

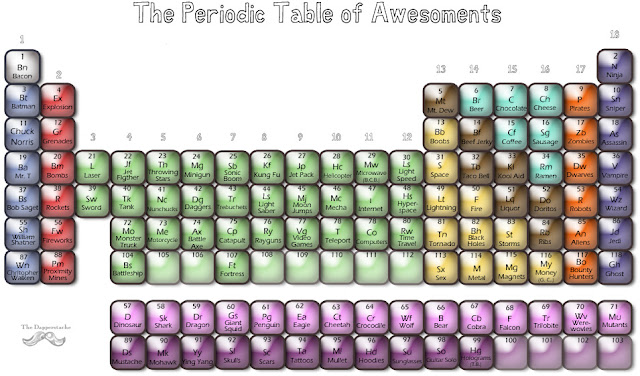

The idea for this post comes courtesy of a classmate who brought this to class.

Second, I want to talk about awesomeness in writing. When I say "awesomeness" I mean a very specific trait. I don't mean what you, as the writer, like. I know a lot of people who geek out over Renaissance literature, and while writing that into a novel will be fine and dandy for them, I don't think it would count as awesomeness. So, what is awesomeness, and why should writers care about it?

The idea for this post comes courtesy of a classmate who brought this to class.

This is a clever list of elements that are generally considered awesome by the public. It's a little dated (mullet? really?), but a lot of these are still awesome.

Here's my definition of "awesomeness": it's the collection of ideas that make you, the writer, and the reader smile and go, "Ooh." These are the things we never quite grow out of being interested in. As a child, we like spectacle, magic, superpowers, royalty, epic battles, and time travel. Which is why I think Doctor Who is so popular. Try to imagine a child, teenager or young adult going to a movie. What are they going to talk about when they come out? Will it be the scintillating dialogue or the deep symbolism? Not likely. They're going to talk about the jokes, explosions, and ninjas.

I'm not advocating throwing literary writing to the wind in pursuit of what will sell. But that which is "awesome" does sell. It keeps readers interested in the story, which is not a bad thing. You can have the most symbolic, high-brow story every written, but what good does it do anyone if no one reads it? The Elements of Awesomeness are also valuable in that many of them introduce conflict or are signs of conflict that already exists. Stories thrive on conflict, especially certain genres.

Final point: when writing an adventure, fantasy, science fiction, thriller, etc., anything that is meant to raise the reader's heartbeat and keep them from putting down the book, add awesome. Keep the thrill ride going. For introspective stories that focus on the importance of the mundane, remove these from the story. You want the reader to find the meaning of small moments, and they can't do that if your hero is walking in slo-mo away from an exploding building.

Tuesday, November 6, 2012

Gut Reactions

Happy November, everyone! I hope everyone's having a good time with the new month, now that the horror posts of Halloween are over. I'm planning some posts about warm, happy stories, but sadly, today is not one of those days. I want to talk about what to do when, in writing a story, you have to describe a physical sensation your narrator is going through.

Personally, I think this is difficult. For one thing, when the narrator is looking at another character who, say, feels like he's going to throw up, he can describe what that person looks like, and it's relatively harmless to do that. Most of the time, when someone is sick, his face turns pale and he sags, right? However, when describing nausea from the narrator's view, you have to describe it more in depth: the illness, the pain, the constant worrying that she, the narrator, is going to lose it. You have to do this in the voice your narrator would use, and much of the time, you have to know how it feels. It greatly helps when writing about feeling sick if you've felt sick.

This is another snag I come up against when writing my narrator's reactions to things. Not just physical illness, but also emotional reactions. I live a very comfortable life. I don't remember breaking any bones, and I haven't been hurt or sick all that much. I haven't experienced crippling loss or mental illness. So, how on Earth can I write from the perspective of characters who have? I can't go out and break an arm every time I want to write about a character who gets injured in that way, and, obviously, I wouldn't want to.

I guess this all comes down to the whole "write what you know" thing. The question I raise is this: is it important to have experienced personally everything your characters go through? I don't think you can, especially when you write fantasy or adventure. Most writers live normal, boring lives, at least, outside their heads. Sometimes you have to bridge the gap between what you know and what your characters know.

So how to fix this? Well, there are some ways I use. Currently, I am writing from the perspective of a character who has panic attacks. I don't get panic attacks, so this is the first thing I do when writing from his viewpoint: I mentally go back to a class I took on psychology, where I learned the symptoms of a panic attack. A lot of writers, when they don't have the personal experience, do research. Interviews, fact sheets, anything they can use to make the writing seem true to what a real life experience would be like. The other thing I do is enhance the experience I do have. I may not know what a panic attack feels like, but I know what it's like to be afraid, and all the physical sensations that come with it.

Combining the two, I feel I can make an accurate portrayal of what a panic attack would feel like for someone experiencing it. This, like everything else on this blog, is just my opinion and personal style of writing. And, as always, I'd be interested to hear other views, so comment away and I'll see you again next week. Don't forget to check out my publisher's Kickstarter. My book, The Shifting, is one of the $25 pledge gifts.

Personally, I think this is difficult. For one thing, when the narrator is looking at another character who, say, feels like he's going to throw up, he can describe what that person looks like, and it's relatively harmless to do that. Most of the time, when someone is sick, his face turns pale and he sags, right? However, when describing nausea from the narrator's view, you have to describe it more in depth: the illness, the pain, the constant worrying that she, the narrator, is going to lose it. You have to do this in the voice your narrator would use, and much of the time, you have to know how it feels. It greatly helps when writing about feeling sick if you've felt sick.

This is another snag I come up against when writing my narrator's reactions to things. Not just physical illness, but also emotional reactions. I live a very comfortable life. I don't remember breaking any bones, and I haven't been hurt or sick all that much. I haven't experienced crippling loss or mental illness. So, how on Earth can I write from the perspective of characters who have? I can't go out and break an arm every time I want to write about a character who gets injured in that way, and, obviously, I wouldn't want to.

I guess this all comes down to the whole "write what you know" thing. The question I raise is this: is it important to have experienced personally everything your characters go through? I don't think you can, especially when you write fantasy or adventure. Most writers live normal, boring lives, at least, outside their heads. Sometimes you have to bridge the gap between what you know and what your characters know.

So how to fix this? Well, there are some ways I use. Currently, I am writing from the perspective of a character who has panic attacks. I don't get panic attacks, so this is the first thing I do when writing from his viewpoint: I mentally go back to a class I took on psychology, where I learned the symptoms of a panic attack. A lot of writers, when they don't have the personal experience, do research. Interviews, fact sheets, anything they can use to make the writing seem true to what a real life experience would be like. The other thing I do is enhance the experience I do have. I may not know what a panic attack feels like, but I know what it's like to be afraid, and all the physical sensations that come with it.

Combining the two, I feel I can make an accurate portrayal of what a panic attack would feel like for someone experiencing it. This, like everything else on this blog, is just my opinion and personal style of writing. And, as always, I'd be interested to hear other views, so comment away and I'll see you again next week. Don't forget to check out my publisher's Kickstarter. My book, The Shifting, is one of the $25 pledge gifts.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)